Google has been testing its prototype car on US roads – it's yet to be trialled in the UK – and revealed some details about how its self-driving cars work. Here we explain some of the technology.

Driverless cars are here already, sort of…

Much of the autonomous technology used in Google's self-driving cars is already found on the road.

You may have seen commercials advertising the Volkswagen Polo's automatic braking or the Ford Focus' automatic parallel parking, which both build on the increasingly common use of proximity sensors to aid parking.

Combine these sensors with the automated-steering technology used for parking, throw in the seemingly old-hat technology that is cruise control and you have the loose framework for a self-driving car.

How many sensors does the car have, and what do they do?

Google’s driverless car has eight sensors.

The most noticeable is the rotating roof-top LiDAR – a camera that uses an array of 32 or 64 lasers to measure the distance to objects to build up a 3D map at a range of 200m, letting the car "see" hazards.

The car also sports another set of “eyes”, a standard camera that points through the windscreen. This also looks for nearby hazards - such as pedestrians, cyclists and other motorists – and reads road signs and detects traffic lights.

Speaking of other motorists, bumper-mounted radar, which is already used in intelligent cruise control, keeps track of vehicles in front of and behind the car.

Externally, the car has a rear-mounted aerial that receives geolocation information from GPS satellites, and an ultrasonic sensor on one of the rear wheels that monitors the car’s movements.

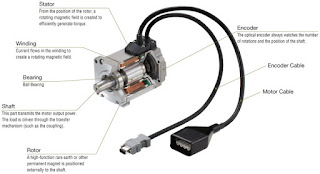

Internally, the car has altimeters, gyroscopes and a tachometer (a rev counter) to give finer measurements on the car’s position. These combine to give the car the highly accurate data needed to operate safely.

How Google’s driverless car works

No single sensor is responsible for making Google's self-driving car work. GPS data, for example, is not accurate enough to keep the car on the road, let alone in the correct lane. Instead, the driverless car uses data from all eight sensors, interpreted by Google's software, to keep you safe and get you from A to B.

The data that Google's software receives is used to accurately identify other road users and their behaviour patterns, plus commonly used highway signals.

For example, the Google car can successfully identify a bike and understand that if the cyclist extends an arm, they intend to make a manoeuvre. The car then knows to slow down and give the bike enough space to operate safely.

How Google's self-driving cars are tested

Google’s self-driving vehicles – of which it has at least ten – are currently being tested on private tracks and, since 2010, public roads.

The car always has two people inside: a qualified driver with an unblemished record sits in the driver’s seat, to take control of the car by either turning the wheel or pressing the brake, while a Google engineer sits in the passenger seat to monitor the behaviour of the software.

Four US states have passed laws allowing driverless cars on the road, and Google has taken full advantage, testing its car on motorways and suburban streets.

Steve Mahan, a California resident who is blind, was involved in a showcase test drive, which saw the car chauffeur him from his house around town, including a visit to a drive-through restaurant.

However, it’s not quite a case of telling your car where you want to go, sitting back and relaxing.

Are driverless cars safe?

This is one of the questions that continues to pop up in the driverless car debate: is it safe to hand over control of a vehicle to a robot?

Supporters of self-driving car technologies are quick to point to statistics that highlight how unsafe the roads are at the hands of non-autonomous cars – in 2013, 1,730 people were killed as a result of car accidents in the UK alone, and a further 185,540 people were injured, according to the Office for National Statistics.

The worldwide figures are just as scary, with road deaths claiming 1.2 million lives last year. Google claims that more than 90% of these fatalities were due to human error.

In April, Google announced that its driverless cars had covered over 700,000 miles (1.12 million kilometres) without a recorded accident caused by one of its vehicles - one was hit from behind, but the other driver was at fault.

While this is an incredibly small figure compared with how many miles UK motorists cover in a year – in 2010, car insurance company Admiral suggested the number could be near 267 billion miles – the fact that autonomous Google cars are still accident-free remains encouraging.